It’s been a year since that day and internet connectivity, including broadband usage, has been restored in the region just a few months ago. However, mobile users still have to use 2G connectivity and there are frequent shutdowns that cut them off. Here’s a look at how this has affected people in the region over the past year, as well as during the pandemic — and what it tells us about the power governments wield over people by controlling access to digital service After India became an independent nation in 1947, Jammu & Kashmir was given a special status under Article 370 of the constitution. While the state has been always a part of India, it had the autonomy to make certain decisions for its people independent from the central government. In addition, citizens of India based elsewhere couldn’t buy land or develop properties in the region. Plus, the state government had its own say in matters such as marriage and divorce, trusts, and ownership of properties other than agricultural land. Jammu & Kashmir was also a border state sharing its lines with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China (the state is now re-constituted as two union territories: Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh) . Because of that, the state had become a place with frequent incidents of militant activity and army movement.. It was the also only state with a Muslim majority. Last year on August 5, Home Minister Amit Shah moved to abolish Article 370 in the parliament. This was controversial as according to the constitution, it could be only be scrapped in accordance with the Jammu & Kashmir state government. However, the state was already under Presidential rule, and the government just needed to get the consent from the governor at that time. Once, the Indian parliament passed this rule, the internet, and all telecom services were put on freeze. Plus, there was a total communication blackout with a block on cable TV and phone lines. Several political leaders were put under house arrest and the government issued a curfew in this area. The blackout meant that people couldn’t contact their family or friends to know if they were safe. The government lifted the ban from landline services on August 16 last year, but it wasn’t till October 2019 when it allowed Kashmiris to use mobile phones again — but only if they had postpaid connections.

Lifting of the ban and its repercussions

In January, after 165 days of internet blackout, the government allowed 2G connectivity with a limited number of sites whitelisted. Later, the list was expanded, and eventually, site restrictions were lifted. During this time, life for people in the region hasn’t been easy. A lot of students were unable to access educational services, and businesses suffered losses because they couldn’t conduct any transactions online. A report released by Kashmir Chamber of commerce in December noted that businesses lost $2.4 billion since the blackout. As per a recent report, that loss has been now extended to more than $5.3 billion. Earlier this year, Buzzfeed’s Pranav Dixit wrote about how the internet shutdown had affected numerous lives in Kashmir. Isma Salaria, a founder of a technology company, had to let go of almost 20 people as operations slowed to a crawl. The CEO of another IT firm there had to fly out to other cities just so he could check his emails and stay in touch with professional contacts. A story by Rest of World highlighted a university student’s struggle in Kashmir, as they had to live with a slow connection and multiple interruptions online. It took them several minutes or even hours to download simple documents for their studies — it would have taken just a few seconds on a 4G connection. In a recent round table discussion related to the state’s interest in controlling the internet, Prof Manoj Jha, a member of Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house of parliament, noted how one PhD student missed several guidance sessions for their doctorate owing to poor connectivity in Kashmir. Software Freedom Law Centre India, a digital rights nonprofit, interviewed numerous business people and students to get a sense of the effects of the internet blackout. These people talked about their experiences and during this shutdown; watch below by hitting the play button. In February, cops in the region registered a case against folks who were using VPN apps to access restricted online services. The complaint was filed under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act intended to curb the spread of rumors and misinformation. The aim of this case was to stop any unlawful activities. To enforce these restrictions, Army personnel reportedly even checked people’s phones to monitor what apps they might be using.

The current state

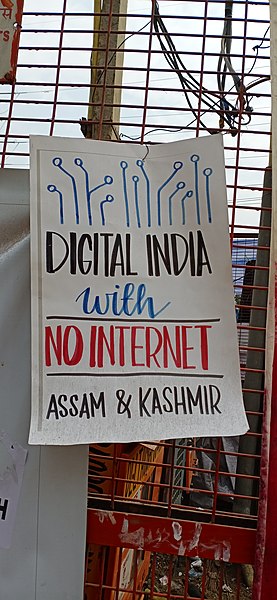

After the coronavirus pandemic broke out, people across Kashmir demanded that 4G internet be restored in the region for a better flow of information and access to technology such as telemedicine. However, there was no respite from the government and medical professionals had to face a lot of obstacles to provide care. Even after a year, Kashmir doesn’t have 4G connectivity and there are still multiple disruptions per month — 7 last month as per internetshutdown.in. In January, India’s apex court passed a judgment that internet shutdowns can’t be indefinite. So, the authorities have passed recurring orders to limit connectivity in Kashmir. Despite enforcing the longest shutdown in the democratic world and amid the ongoing pandemic, the government is still not ready to restore full connectivity in Kashmir. On the one hand, Prime Minister Narendra Modi often talks about Digital India and Make in India innovations, but on the other hand, there’s been no effort to reinstate digital freedom in the region — and that’s a worrisome sign. The Modi government’s argument for scrapping Article 370 was to control terrorism and create job opportunities. However, Kashmiris had no say in this, and more importantly, they couldn’t register any of their views because of the communication blackout. In 2020, a lot of your daily activities and freedoms rely on the availability of internet services. Imagine if someone took that away with the flick of a wrist, a signature on a sheet of paper. As anyone in Kashmir can tell you, that grim reality may not be so far-fetched.