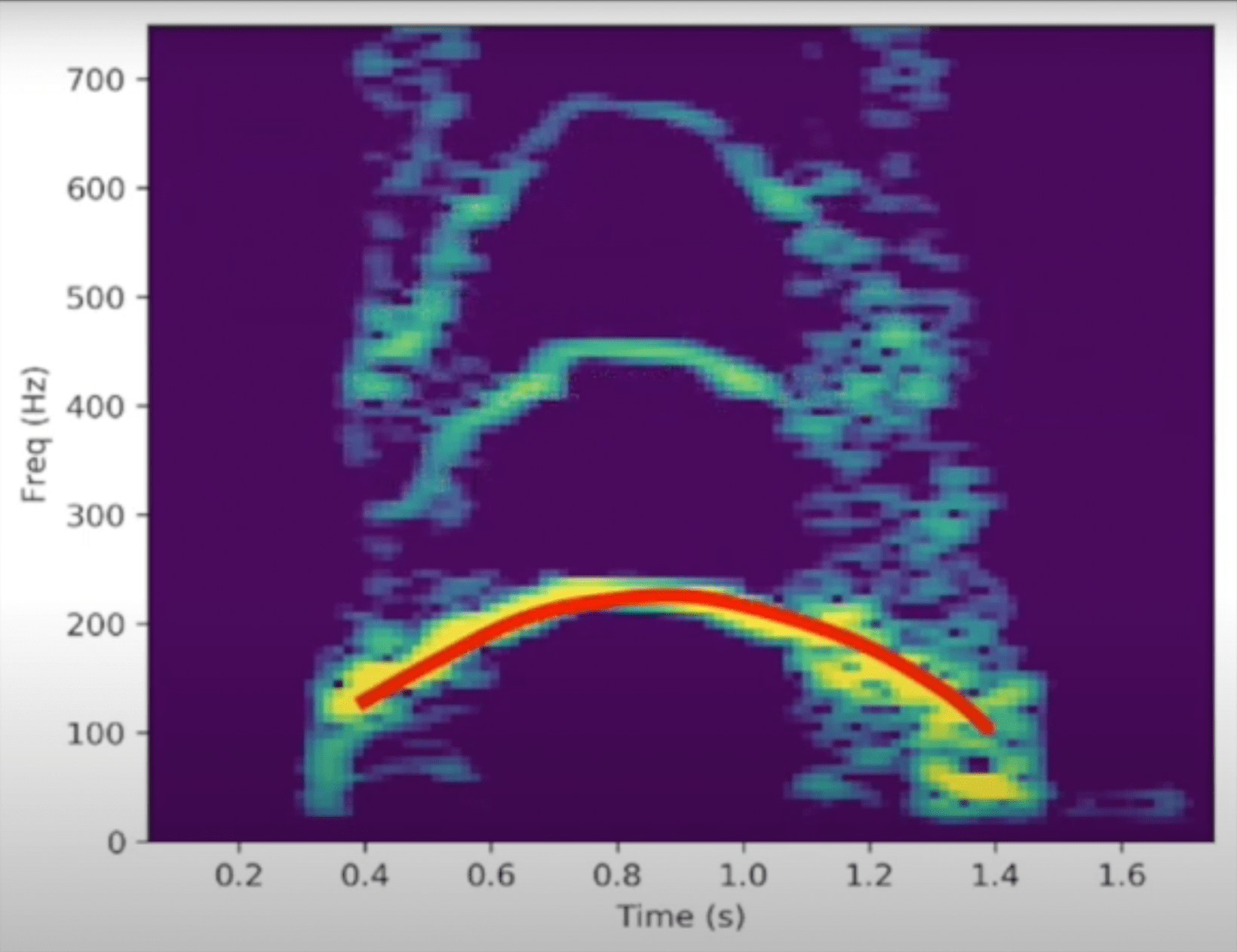

Previous research has shown that lions roar to communicate with other members of their pride and scare off foes. But we still know little about how they recognize which animal has made the call. The Oxford scientists tried to find out by designing a device called a “biologger” that’s attached to a lion’s existing GPS collar to record audio and movement data. They then associated each call with a lion by cross-referencing the data through their recordings of roars. [Read: This AI system thinks we’re getting better at wildlife conservation] Next, the team used the data collected by the biologgers to train a pattern recognition algorithm to recognize each lion’s roar. Finally, they tested the algorithm on recordings it had not been fed before. They found that each lion’s roar produces a distinctive frequency shape. The algorithm used these to match a roar to an individual lion with 91.5% accuracy. The system was developed by researchers from Oxford University’s Department of Computer Science and WildCru, the conservation unit that had been tracking Cecil the Lion until he was killed by a trophy hunter in 2015. His death sparked an outcry that forced the hunter into hiding. Identifying the roars of other lions could help protect the roughly 20,000 of them that are still left in the wild. “African lion numbers are declining and developing cost-effective tools for monitoring, and ultimately better protecting, populations is a conservation priority,” said WildCRU’s Andrew J. Loveridge. “The ability to remotely evaluate the number of individual lions in a population from their roars could revolutionize the way in which lion populations are assessed.” You can read the full research paper in the journal Bioacoustics.